Rooms: Investigating Cities & Their Music by Jonas Vogt

24th September 2021

Illustration Chloe Scheffe

Foreword by Dominic Flannigan

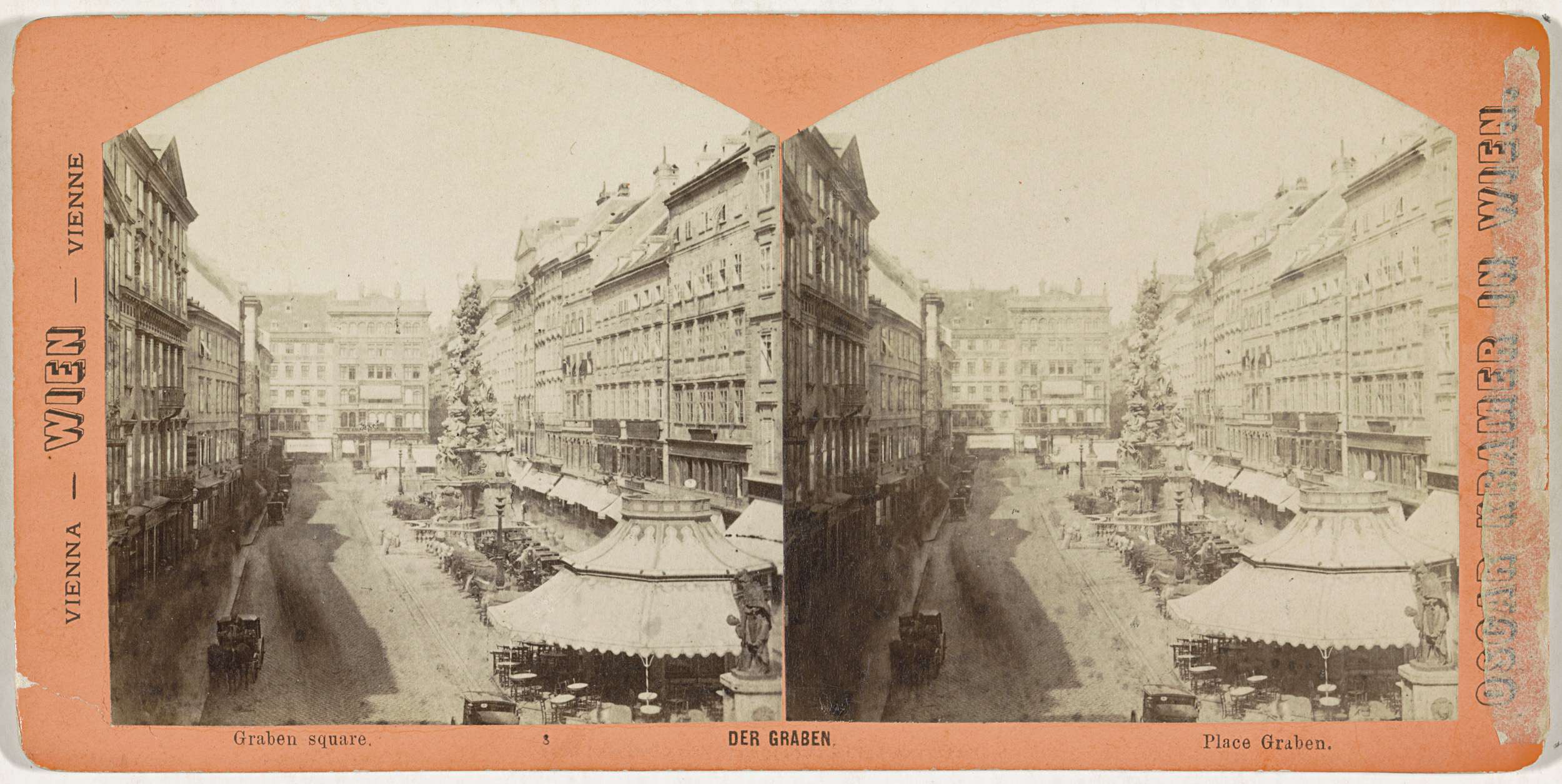

As LUCKYME® first emerged we returned to play multiple shows in Vienna, a city which played a very particular role in the development of our music. Very few UK or American writers have picked up on the energy of Vienna but this city has quietly spawned three generations of jazz-influenced beats and electronic music. The parties we saw first hand were absolutely packed and often in very well spec’d spaces right in the middle of this historic city. Deep underneath some vast municiple building, the front row chanted the words to a Three Six Mafia bootleg. Underneath litter-free pavements, Vienna crowds would come pristine but leave in shambles. We’d roll out of the Pratersauna club at dawn (a club built literally within a sauna) and head straight to the Praterpark (literally a themepark). At a time us Scots were all drinking cheap spirits our hosts in Austria were sipping grüner veltliner at dinner. They just always seemed to do it right. They were the young upstarts of their city, but they carried themselves into these great white tablecloth resturants as if they deserved to be there. It felt completely different to the way we acted in Glasgow.

At the first Brainfeeder party I watched a room of people treat Dorian Concept rip on a single octave keyboard with a mosh pit in front of him. Now that we’re friends with these guys, something we often discuss is how those virtuosic jazz-fusion groups of the late 70s seemed to lose that raw spirit from their music. Something about being that good at your instrument tends to put you on a high stage at a well-lit jazz festival. But what we saw in the music of Cid Rim and Dorian Concept was that guys who could completely own their instrument were playing advanced music at high volume right in front of fans of club music and rap music and it was working! It was a riot. Look, punk is cool... but let’s not overlook every kid who knows what they are doing. In Vienna we saw a bunch of artists steeped in jazz, idm and hip hop making something original from the pieces. Creating local scenes, we related to their sense of distance from the “music industry”. And perhaps this feeling you had to first create something here, at home, is why we’ve signed artists in Montreal, Glasgow, Vienna. These aren’t places people write stories about but these are the places where people write great stories. Great scenes pop up in the secondary cities, where they perhaps have less opportunity for success, but more space to get good.

Songs of Vienna is a work which not only seeks to express Cid Rim’s upbringing, but speak to this particular moment for the Austrian capital. While the record blooms with psychedelic colour and optimism, there’s also a threat which pulses throughout. Lyrics hint at the decline of the European project and the rise of populism; and the war between the financial system and climate action. All this shows up beneath these strange post-post-modern psyche songs, drafted during pop writing sessions in London and LA. But like all good pop, what makes this such a compelling record is that it does this with a degree of joy. Without losing its point of view. Like Vienna, the album is both progressive and classic. Priviledged and decrepit. Deft and relaxed. And so to commemorate the release of Songs of Vienna, we asked journalist Jonas Vogt to explore his home town of Vienna and consider how music in general might emerge from place.

Cid Rim photographed by Mato Johannik (2021)

Rooms

This piece has been translated from German to English.Stuart Cosgrove was onto something big, and maybe he didn't know it. In 1988, the Scottish music journalist wrote the liner notes to one of the world's first techno compilations: Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit. Almost all the early protagonists of Techno have their say in just under 5000 characters: Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May. One of the most famous statements about Detroit Techno: "The music is just like Detroit, a complete mistake; it's like George Clinton and Kraftwerk are stuck in an elevator with only a sequencer to keep them company" forever immortalized by Cosgrove.

In a somewhat lesser-known section, Derrick May describes his hometown, painting a bleak picture of a community in disintegration. “Factories are closing and people are drifting away. The old industrial Detroit is falling apart, the structures have collapsed. It's the murder capital of America. Six year olds carry guns and thousands of black people have stopped caring if they ever work again." And then a telling line: "If you make music in that environment it can't be straight music."

Cid Rim - a friend of mine whose career I've been following for almost 10 years now - has now made an album called Songs of Vienna. And indeed, you can hear the city where he grew up (and I currently live) coming through in each track. It's reflected without being able to name exactly why. And of course, this is not the first album in the history of music that you can say something like that about.

There is music that is inextricably linked to the places it was created. Grunge is unthinkable without Seattle, Hip-Hop without New York, Country without Nashville. The links self-evident because we perceive music as the cultural product of place, time, and the people. We assume that the characteristics, the very essence of a city, seep into what is created within. To use a continental metaphor, like the smokehouse flavoring the ham. Detroit is a very good example of this: in the city's heyday, the happy, optimistic sound of Motown defined a boom era. In its decline, Techno emerged. The same people. The same city. Only the smoke had changed.

If you look at the cities that have shaped musical styles (or at least local varieties of them), it's not so easy to find a common denominator. There are thriving metropolises among them: London, Berlin, New York. Cities that never sleep, where you can have anything at any moment and anything can happen. In a New York Minute, everything can change.

But there is also the opposite. Cities in decline that offer few jobs, no entertainment, bored youth and cheap speed. Manchester, Marseille, Linz. "Tell them I know gangsters outside KFC" is what the Lotto Boyz' Birmingham Anthem says. Something like that is very, very far away from New York, literally as well as metaphysically. Maybe you could say this: There are cities where a creative music scene emerges because the whole city is creative. And there are cities where that happens because the rest of the city is so boring. How does that happen?

Seeing Patterns

It’s said historians should ask these questions: "what happened?", "when did it happen?" - both of which seem straightforward. The most difficult is the perhaps “why did it happen?” and further “why did it happen there?”

Theories as to why a music developed in a particular city are often very mature, reaching back years. Accepted theories like a highway was partly the reason for the emergence of Hip-Hop: the Crossbronx Expressway, built between 1955 and 1963 across black neighborhoods tore apart established communities. But in turn, cleared the ground for spaces where rap would emerge.

You have to be a little careful about things like that. People tend to see patterns in things that deserve deeper analysis. Precisely because questions three and four are so difficult to answer.

There are definitely examples that defy sociological interpretation. One of the most important centers of the second wave of Minimal Techno in the early noughties was Cologne. There is no plausible, singular explanation for the emergence of the "Kölner Schule" that can be used to fill scientific papers. Just a few names and a label: Wolfgang Voigt, Jürgen Paape and Kompakt. Often at the core of such stories is a simple process: there is a center of gravity consisting of a handful of strong protagonists, a label and/or one or two venues. It starts to spin stronger and stronger and attracts new people. At some point, a fragile structure of individual elements emerges, which don't even have to be that close to each other. And usually a name is found for it. The British cultural scientist Steve Redhead has shown in a famous study of British rave culture that the construction of scenes often only takes place when their "golden years" (usually only framed as such in retrospect) are over. By the time Rave was perceived as a unified scene, it was already in decline. To put it more simply: the most important protagonists of a movement do not know for a long time that they are part of a movement.

It hasn't been that different in Vienna in the last 10 or 15 years. The protagonists of a certain Viennese sound (still un-named at the point of writing) - Dorian Concept, The cloniOUs, Cid Rim and a few others - can be traced back at their core to a loose scene from Jazzwerkstatt, the Viennese districts of Neubau and Josefstadt and the Affine Records label (run by Jamal Hachem). There was a historical moment - probably around 2011-2014 - when this sound got a lot of attention as an expression of the city. But it’s fair to say it existed years before and years after. The last "Loud Minority" parties, also an important nucleus for local and international talent, took place in 2012.

If you ask the musicians, the journalists, the promoters why the music from Vienna - be it the downtempo of the 90s or the jazz-infected electronics of the last decade - sound the way they do, they usually think of a few characteristics of the city: The Gemütlichkeit (cosiness), which can be as oppressive as it is relaxing. And the music colleges flood the city with plenty of trained young musicians. That's all true but leaves out a vital aspect: there was space in the city for everything to develop.

Multidimensional spaces

When culture speaks of spaces, is usually holds a double meaning. It does indeed mean rooms made of stone and mortar in which one can rehearse, play or experiment. But also in the figurative sense as spaces to grow and evolve without the pressure of expectation of critique or industry scrutinising you. We need structures to offers space for new ideas to spread. Or sometimes the very lack of structure which gives people the opportunity to develop their own institutions. We need niches and spaces in the market of attention, without which culture cannot survive.

Space can take many forms. And it is through analysing space that we can best answer why New York, Marseille and Manchester served as the birthplaces of their own style. In New York, there are countless small venues in which to play concerts; new bands can grow in the shadow of larger ones; and with a highly saturated, highly discerning audience finally, a certain hunger for novelty is bound for success. In Detroit of the '80s, things were different: the “City of Tomorrow - Today!” was falling apart. With no lack of physical space in the post-industrial sprawl, no one expected the next spark of urban futurism in Techno, to emerge from the young, black and disenfranchised of Detroit. While Vienna offers space and opportunity in cheap rehearsal rooms and conservatories, their priviledge fights against Wurschtigkeit (doesn’t-matter-attitude) - a certain Austrian detachment that can mean young people don’t ever feel they should be taken seriously.

But to answer the question of how the nature of a city affects its culture, historians could rush to think chronologically (X + Y = Z). But this linear understanding is misleading when it comes to the question of how a city and its music are connected. It is more multidimensional. People who make music need an environment, they need soil in which to grow. But they also happen to nourish, shape and fill this ground at the same time. Analogously, this applies to the people who act: The essence of a city, whether bustling or Wurschtigkeit, is found in the people who have grown up and live in it. And this changes their veryessence. And through all this complex system of preconditions, design, rejection and occupation of space, the city, the environment finally finds its way into the music. It is not a simple arrow. X does not lead to Y. You can’t reduce this to a construct. The people, the spaces and the music influence each other in a plethora of ways - exchanging in all axis to produce the corporeal reality of the culture.

Virtual Space

These principles are valid, whether we're talking about the Beatles, New Order or Hudson Mohawke. But the 21st century is somewhat different to its predecessors. It created a whole new place beyond topography. The moment in which this came into being can be named relatively precisely: It was 2003, when American Tom Anderson founded MySpace. Myspace was a virtual space in which subcultural scenes of music could incubate and communicate. Just as Napster allowed people to discover and consume music without needing the indie record store as a physical location, MySpace meant there was no longer a need to be rooted in the local. Musicians had been sharing across the globe before, but it was the metaphor of identity that opened up our notion of this community, and took it to a whole new level. Music people got to know each other through MySpace, for three influential years as the primary place online to boost about music, show affinity with other artists and demonstrate your music to the public.

Probably the most important thing about MySpace is that we don’t think of it as a negation of a gig. If you see the emergance of these networks as a way to overlook the real world, you missed the point. They opened new paths and new spaces, made things possible that were not possible before. Suddenly, Scottish producers could collaborate with Canadian rappers, with little friction and basically without ever meeting. Over the last decade, cascading stories of friendships formed online have created transnational music and topped charts. All music is electric and all music moves through this virtual space. It is creative space and resonating body at the same time. And here, too, it's reciprocal: like all other spaces, it changes the people who move through it. And they in turn, change it.

The relationship between city, artist and space is multi-dimensional, and the digital has made it no less multi-layered. Today a musician like Cid Rim can move between London, Glasgow or Los Angeles, and their existence is seamless in our digital space. His indentity, however, is fixed in place. When I first asked him why the album was called Songs of Vienna, Cid Rim said something that perhaps symbolizes this ambiguity perfectly: “well, the album was mixed and finished there through lockdown” and further "... I don't think I can make a non-Vienna album, no matter where I am."